Winter Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) and its milder form, Sub-syndromal SAD (commonly known as Winter Blues or Winter Depression), affects nearly a third of the UK adult population. So even if you don’t suffer from one of these conditions yourself, it’s highly likely that someone close to you does. Read on for your guide to SAD and Winter Blues.

We’ll cover:

- What is SAD?

- How does SAD make you feel?

- How common is Winter SAD and Winter Blues?

- What causes SAD?

- Is SAD real?

- Diagnosing and managing SAD

What is SAD?

SAD is a type of major depression that comes and goes in a seasonal pattern. In the UK, SAD is diagnosed by NHS professionals using the International Classification of Diseases 10th edition (ICD-10) and in the US and Canada by using the American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) criteria. Rather than being a separate condition, SAD is considered a variant of clinical depression where only depressive states occur, and bipolar disorder where both depressive and manic states occur.

While Winter SAD is thought to be the most common and has received the most research attention, some people experience a summer variant which has some different symptoms and seems to have different triggers. It’s also possible to experience spring and autumn SAD, as well as Hesperian depression, known as sundowner syndrome, though these are thought to be rare. Because of this, most people mean Winter SAD when they talk about this syndrome and it’s the one I’ll focus on in this article and where we talk about SAD elsewhere on this website unless otherwise stated. We’ll take a look at the other variants in future articles.

For you to be diagnosed with any variant of SAD, your GP would need to rule out other conditions that have similar symptoms and you would need to have had similar symptoms for at least two years in a row that start and resolve at the same time each year. You won’t have these symptoms at any other time of the year.

How does SAD make you feel?

One of my favourite shorthand ways to describe how Winter SAD makes you feel is through the Tigger and Eeyore characters from Winnie the Pooh, as I find most people are familiar with them and their personalities.

During the autumn and winter months, the shorter days and lack of sunlight can trigger us to feel down, irritable, lethargic and unsociable – a bit like Eeyore. But in the spring and summer months, we often tend to feel more ‘ourself’, with high energy levels and a more upbeat mood, like Tigger. Sometimes, if we experience the bipolar form of SAD, we find that spring triggers hypomania – a state of overstimulation that makes us feel excitable, impulsive and highly energised. This can be fun, but can also feel quite uncomfortable and lead to impulsive decisions and behaviour that we may later regret.

There are many symptoms associated with experiencing SAD and you might not have all of them all the time or at the same intensity; some you might not experience at all. Many of them overlap with symptoms experienced in other common conditions/traits, such as Vitamin D deficiency, anaemia (iron deficiency), thyroid dysfunction, fybromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), sensory processing sensitivity and others. If you have other conditions, you may notice a seasonal pattern to the symptoms’ intensity. This is why it is important to consult with your doctor rather than self-diagnosing, so your doctor can investigate and rule out other conditions. In addressing any issues found with e.g. nutritional deficiencies, you may still have SAD, but at least some of your symptoms may be improved.

The following symptoms describe what you might feel in autumn/winter, in the depressive state. We’ll look at hypomania and mania in another article.

Physical symptoms:

- Low energy/sensations of being weighted down (fatigue)

- Increased appetite and cravings for simple carbohydrate-rich foods

- Sleep disturbance (oversleeping, napping, restless sleep)

- Weight gain/loss

- Muscle tension, pain, stomachache, headaches

- Lowered immune response

- Decreased libido

Emotional/cognitive symptoms:

- Feeling depressed, sadness, tearfulness

- Feeling anxious

- Decreased enjoyment of activities you normally enjoy

- Social withdrawal

- Lacking motivation

- Irritability

- Trouble concentrating, forgetfulness, ‘brain fog’

- Being ‘down on yourself’, feeling shame and beating yourself up

- Negative thoughts generally

- Thoughts about harming yourself

People with Winter SAD will usually experience their depressive symptoms for about five months, often beginning around October and continuing until spring. As full-blown symptoms of SAD are often debilitating, this is distressing for us as individuals, and can also be difficult for the people we share our lives with.

These next few paragraphs on the way we think about SAD and how it makes us feel may be triggering, so please feel free to skip over them to the next section, if you want.

Common thoughts and feelings

From personal experience and conversations with other people who experience SAD, I have found that these kinds of thoughts are common about how it affects our lives:

- I’m living a ‘half-life’

- SAD steals so much of my life

- I only fully live or feel ‘myself’ during spring and summer – I don’t feel ‘myself’ during autumn and winter

- It’s like a ‘life sentence’, knowing it’s a recurring condition and its pattern

- I dread the autumn and winter

- I just want to hibernate but obviously, that’s not an option!

- I’m not tired because I’m depressed; I’m depressed because I’m tired

We often find ourselves ruminating, trying to figure out why we feel this way, what we can do about it, why other people seem okay and we’re not. We tell ourselves off, feel guilty about how we behave, how we feel, how we’re thinking – and it spirals.

When we have been symptomatic during the autumn and winter, those of us with the bipolar variant of SAD sometimes emerge into spring with hypomania. We might feel a mixture of excitement, frustration and impatience to get on. We often think that we’ve just ‘wasted’ half the year and have to make up for it – we now only have half the year to achieve all our goals. This can make us quite ‘gung-ho’ and we might spot patterns of when we have taken or pushed others to make big decisions that we later felt weren’t right, or wondered why we were so impatient. We often expect that we should be able to perform at our spring/summer high energy level all year round, so we push ourselves through autumn and winter. We ignore what our bodies are telling us (to slow down) and this often seems to lead to cycles of burnout.

If this is resonating with you, I hope that it helps you to know that you’re not alone. Even if other people around you don’t experience full-blown SAD, they may at least share some element of what you experience, albeit with milder, less debilitating symptoms.

How common is Winter SAD and Winter Blues?

In the UK, where we experience significant changes to our day length and weather patterns throughout the year, research by The Weather Channel and YouGov in 2014 and by Holiday Gems and One Poll in 2018 found that the majority (over 50%) of adults in the UK experience negative changes to their levels of energy, activity and their overall mood in the autumn and winter months.

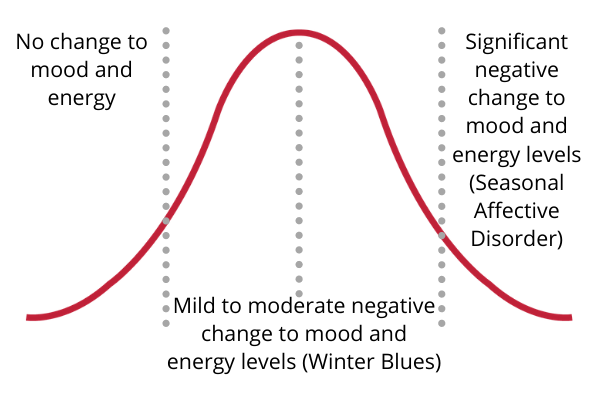

The Weather Channel research found that 29% of the UK adult population experiences SAD to a degree. Of these, 8% of UK adults considered they suffered from diagnosed SAD – twice the rate as previous estimates. A further 21% considered that they suffered with Sub-syndromal SAD, commonly known as Winter Blues.

We can describe this using a bell curve, or normal distribution curve, as SAD is a continuum – the one shown here is just for illustrative purposes. In the UK and other places of similar latitude, the majority of people will experience mild to moderate negative changes in their energy and mood in the autumn and winter months – Winter Blues. At either end of the scale, you have fewer people who don’t notice any changes to their mood and energy, and people who experience significant changes that are enough to disrupt their lives and be diagnosed with Seasonal Affective Disorder.

There has been a lot of debate over the latitude hypothesis and exact rates of SAD in different populations. One study reviewing the literature found a significant positive correlation between latitude and prevalence in North America, but it was only a trend in Europe. They concluded that the effect of latitude was small and ‘climate, genetic vulnerability and social-cultural context can be expected to play a more important role’. A Greenland study found that people living in northern areas were significantly more likely to have SAD. Another found evidence of the link when including all countries and only peer-reviewed articles.

It is not yet fully understood why, but research has also shown that SAD affects younger women most. In reproductive years women experience SAD at a ratio of 4:1 compared with men. In childhood and post-menopause, there’s no difference between the genders.

What causes SAD?

Science hasn’t yet been able to find an exact cause for SAD. There are many different areas of research which separates triggers (or stressors) – that are often there for everyone – and vulnerabilities that cause individuals to experience SAD in response to these triggers. Research so far has shown that for the depressive state, the main trigger appears to be day length (photoperiod) and the reduced light intensity that we receive during autumn and winter months.

There seem to be multiple biological and psychological factors that can cause individuals to experience SAD, rather than a single identifiable cause. Light is the common factor – our body’s response to it or its lack, and our psychological response to it. Because of this, in the last decade, researchers have called for and begun to study SAD in a more integrated way.

Biological differences in response to light cues

One popular explanation is that in some vulnerable individuals, reduced exposure to sunlight in autumn and winter causes our body’s internal clock to become out of step with the day (phase delay or phase advance). This leads to chemical imbalances that affect many different functions in our bodies, producing the wide variety of symptoms we experience.

At higher latitudes, our day length changes significantly throughout the year, affecting the amount of light to which we’re exposed. A part of the brain, the hypothalamus, needs a clear difference between bright days and dark nights to make our body work properly. In autumn and winter, the shorter days and reduction in light is thought to be too weak for vulnerable individuals, so the hypothalamus does not get the clear signal it needs.

In our eyes, we have cells that respond to light in our environment – these are called intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs) and they contain a photopigment called melanopsin. Light travels from our eyes through these cells, through our optic nerve and optic chiasm to the master clock (called the suprachiasmatic nucleus, or SCN for short) in our hypothalamus. This link from our eyes to our hypothalamus is called the retinohypothalamic tract.

All the cells in our bodies have their own clocks. The master clock keeps them all synced with the time of day by using environmental cues – especially light received through the eyes. It controls the other clocks through the endocrine system in a roughly 24-hour cycle, known as the circadian rhythm. The hypothalamus is one of the glands in the endocrine system and it works together with the pituitary gland to control all the other glands in the endocrine system to produce the hormones our body needs to remain healthy. The hypothalamus is constantly trying to maintain a balance in our bodies (known as homeostasis), receiving feedback and sending signals. I find it helps to imagine it like a conductor and an orchestra.

What if in some people, there’s a reason that the master clock (the conductor) doesn’t receive the right light signals and so it doesn’t pass the right messages to the rest of the endocrine system (the orchestra)? We end up with a body that is playing out of tune. Once one thing is out of balance, it causes knock-on effects elsewhere in the body. This is what researchers are trying to uncover – but it’s a complex field of science, as you can see.

Researchers have proposed several biological mechanisms that correlate with people experiencing SAD, but no one explanation accounts for all cases. These include the eye not being sensitive enough to light and genetic variations that relate to the circadian clock, the melanopsin photopigment in the eye, and imbalances in hormones such as serotonin (also a neurotransmitter), melatonin and active thyroid hormone.

Negative thinking and behavioural patterns

Researchers in the field are generally accepting of there being environmental triggers and biological vulnerabilities related to SAD. They are also keen to understand whether there are psychological mechanisms that make some people respond differently to these triggers and vulnerabilities.

This is a newer and much smaller area of study, but it is delivering some very promising insights and interventions. Researchers have been investigating whether individuals with SAD are more likely to have dysfunctional attitudes, a greater tendency to ruminate and a negative explanatory style. These thinking styles can lead to behaviour that worsens how we feel.

For example, if we believe that winter is a miserable time and there’s nothing we can do about it, we may hunker down and hibernate. We’ll become more inactive, not socialising, choosing the TV or an early night instead of some of the hobbies we enjoy. These behaviours then affect how we feel, leading to a negative cycle of feeling low in energy, motivation and mood, so we do less, and this further affects our mood and energy.

Is SAD real?

This is a question we hear a lot. Personally, when I have done media interviews over the years to help raise awareness and help others, I’ve sometimes been abused by people who don’t believe it is a ‘real thing’. The acronym, SAD, doesn’t help with the teasing, to be honest! I’ve been told that we ‘can’t get depressed because of weather’, ‘everyone feels like that in winter’, so we’re ‘snowflakes’ and we need to ‘just get on with it like everyone else’.

This can be hard to take when you’re struggling with this syndrome year in, year out and feeling like it steals half your life. When you know that you are super productive and positive for half the year and then SAD sneaks up on you again and makes you feel like a different person. The reality is, most of us are ‘getting on with it’ as best we can. We experiment with what research has so far shown us might be helpful and hope for more breakthroughs.

I’ve chosen to lead with an emotional response to this question. I’ve lived with this condition myself since my late teens – so as I write, for 20 years I’ve been learning how to manage and try to thrive with this condition. I’ve been helping others with it in small ways since 2012 alongside working full-time roles, studying, volunteering and running the Little Light Room blog and events, which has now evolved into Make Light Matter. I feel frustrated when people invalidate other people’s experiences without even trying to understand. It feeds the stigma and stops so many people getting the help they need.

And what about the non-emotional response? The weight of research evidence shows that SAD is a real syndrome and that it is fairly common in many countries at higher latitude, with up to 10% of the population experiencing it, depending on where you are. As it’s a continuum that is normally distributed in these populations, most people experience the milder Winter Blues form that isn’t classed as a clinical problem. SAD is included in both the DSM-5 and ICD-10 diagnostic manuals. It has clinical diagnostic criteria that researchers use to identify subjects for research and compare them with controls who don’t have SAD. First-line treatments have been identified that have been shown to reduce or resolve the symptoms at least while the treatment is ongoing and in the case of CBT-SAD, may provide long-term prevention.

It is in the nature of scientific research to critique and doubt – it’s how progress is made. Research into SAD has made amazing progress in the 30-odd years since the syndrome was first described with this name. It was only in the early 2000s that scientists discovered the existence of the intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells in humans. Since then, many discoveries have been made about how light affects our physical and mental health, but it’s still a relatively young field of research.

The main doubts and debate in the field are around whether SAD should be classed as a separate condition to other depressive and bipolar disorders and in its causes, which most researchers accept are likely to be multi-factored. One often-cited study in 2016 declared SAD to be ‘rooted in folk psychology’. Others have shown exceptions to the latitude hypothesis, e.g. the Tromsø Study, and that Icelandic people seem to experience low rates of SAD. Some, for example, Eagles (2004) have suggested SAD is an evolutionary adaptation.

Diagnosing and managing SAD

As an individual who experiences the collection of symptoms known as Seasonal Affective Disorder – or a doctor or therapist faced with a patient with symptoms – where does all this debate in the field leave us?

In some ways, identifying what helps SAD has been easier than pinpointing what causes it. There is a good body of research as well as lots of anecdotal evidence from consumers that makes bright light therapy delivered by specialist light boxes a first-line treatment for SAD. This treatment is widely accessible and quick, with most people feeling better within a few days to a couple of weeks. One of the frustrations with this treatment is that it only helps when you actually do it. Once you stop, symptoms return. This means that if you’re not great at keeping to a routine for whatever reason, you won’t get the best outcome from light therapy. We recommend speaking with your doctor or a psychotherapist before starting treatment with light therapy. This is because they need to rule out other causes of your symptoms, because it isn’t suitable for some individuals, and so that they can monitor how you get on with the treatment.

If you find waking up in the morning difficult, you can get alarm clocks that wake you up with gradually increasing light, often known as dawn simulators. These are not the same as SAD lights and they’re often a helpful addition to bright light therapy. Some manufacturers have started to create small models that combine a dawn simulator and a SAD light.

A five-year study led by Dr Kelly Rohan at the University of Vermont is delivering exciting insights and positive interventions, building on her team’s previous work. The team are demonstrating the effectiveness of using Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) that is tailored for Seasonal Affective Disorder (CBT-SAD). The results are promising, showing it to be at least as effective as light therapy and more effective at preventing or reducing future SAD. This has led to it being considered another first-line treatment. The new study is particularly exciting because its design involves follow-up of participants in future years and the researchers are assessing biological and psychological mechanisms together.

Sometimes doctors will prescribe antidepressants to treat SAD, usually selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). This will be the right option for some people, but it is not considered a first-line treatment because they take months to fully get into your system. Going on and coming off them can also be difficult for some people, who experience a lot of side effects.

A healthy lifestyle is one that incorporates light nutrition as part of the wider wellness jigsaw. Getting outside into natural light every day, ideally in the morning, will help most people. Diet, exercise and getting enough sleep support all our body’s systems.

If you suspect that you might have SAD or Winter Blues, speaking to your doctor should be your first step. While we say not to self-diagnose and to get support with treatment, this is different from being aware of your own health and the changes in it. Your doctor will find it helpful if you can keep notes on the timing and severity of your symptoms as they happen, along with anything you notice that seems to improve them.

I hope you find this guide helpful. Please comment below if there is anything else you would like me to include in future updates of this article.

Image credits:

Tigger and Eeyore: https://www.clipartmax.com/middle/m2i8d3K9b1d3b1Z5_tigger-and-eeyore-tigger-from-winnie-the-pooh/

Pingback: Lifestyle tips to manage SAD and Winter Blues symptoms

Pingback: How can I manage SAD? Light Therapy | Little Light Room

Pingback: What is Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) and Winter Blues?